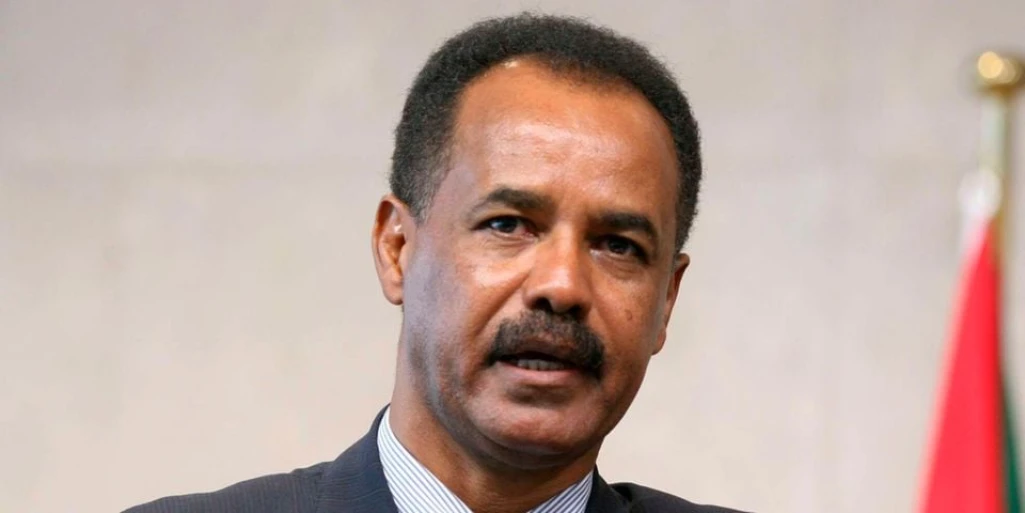

A revered hero of Eritrea’s independence struggle, Isaias Afwerki has ruled with an iron fist for three decades, crushing all opposition and transforming his country into an African “North Korea”.

But the rapprochement did not lead to a loosening of his grip on Eritrea, which was liberated from Ethiopia in May 1991 and declared formal independence two years later.

Long accused of seeking to destabilise the Horn of Africa, Isaias sent troops into Ethiopia in late 2020 to support Abiy in his fight against the Tigray People’s Liberation Front — the country’s former ruling party whose enmity with Isaias dates back decades.

The Tigray war ended in November 2022, with Eritrea sanctioned by the United States over accusations of severe rights abuses by its troops — allegations Isaias likened to “fantasy” at a rare press conference in Kenya in February.

Isaias, now 77, was once hailed as a beacon of hope for Africa but later described in leaked US cables in 2009 as Eritrea’s “isolated and mercurial… unhinged dictator”.

Authoritarian and austere, Isaias commanded a remarkable rebel army in a bitter 30-year struggle against a far larger Ethiopian adversary that was backed first by the United States, then the Soviet Union.

As Eritrea’s first president after independence, then US president Bill Clinton referred to him in 1998 as part of a generation of African “renaissance” leaders.

But several months later Isaias entered into a brutal two-year border war with Ethiopia that left tens of thousands of people dead.

Eritrea’s system of harsh national service has inspired descriptions of the nation as an “open-air prison” akin to North Korea.

‘I don’t feel anything’

Born in February 1946 in Asmara into an Orthodox Christian family, Isaias moved to Ethiopia’s capital Addis Ababa to study engineering but left, aged 20, to join the rebels fighting for Eritrea’s independence.

A charismatic orator with a fearsome temper, Isaias trained in China during the Cultural Revolution, before rising through the ranks of a well-organised movement whose guerrillas dug a warren of bunkers to hold out against Ethiopian fighter jets.

The rebels finally liberated Asmara on May 24, 1991, formally proclaiming independence on the same day two years later following a referendum.

The famously controlling and unsentimental Isaias quickly moved to cement his dominance, at the time telling US journalist and academic Dan Connell: “We’re just getting started.”

“After the referendum, I sat in his office and I said, ‘You know, you’ve spent all these decades in the bush fighting for this moment. Now that you’re here, how does it feel?'” Connell recalled.

“He was so thrown by the question ‘how does it feel’ that he couldn’t answer it. He said, ‘I don’t feel anything. I’ve got a lot of work to do.'”

Eritrea adopted a constitution in 1997, but it has never been implemented and no elections have taken place.

He closed all independent media and jailed critical journalists. The latest Reporters Without Borders press freedom index places Eritrea close to the bottom globally.

He also shrugged off international condemnation, including for throwing out a UN peacekeeping mission and expelling international aid agencies as part of a draconian policy of self-reliance.

Fearing assassination attempts

Isaias railed against corruption after taking power, and has largely shunned the cult of personality beloved by other African strongmen.

His portrait is not on the country’s banknotes and is rarely seen outside official buildings.

But while nominally under civilian rule, Eritrea under Isaias has been carved up into zones of control by army generals, who run flourishing networks of corrupt businesses.

Keen to cultivate a “man of the people” image, he has been known to take regular evening strolls down Asmara’s streets, popping into smoky bars for a drink.

As the years have passed, he has reportedly grown increasingly paranoid, fearing assassination attempts he said were backed by the US spy agency, the CIA.

Under Isaias, Eritrea has become one of the world’s most isolated states, with China and Russia among its few allies.

His alleged regional meddling and support for armed groups in the Horn of Africa — including the Al-Qaeda-linked Al-Shabaab — triggered international sanctions against the regime that were lifted in 2018.

Yet with opposition figures jailed or exiled, few can imagine an alternative to Eritrea’s unelected president with no-one lined up to replace him.